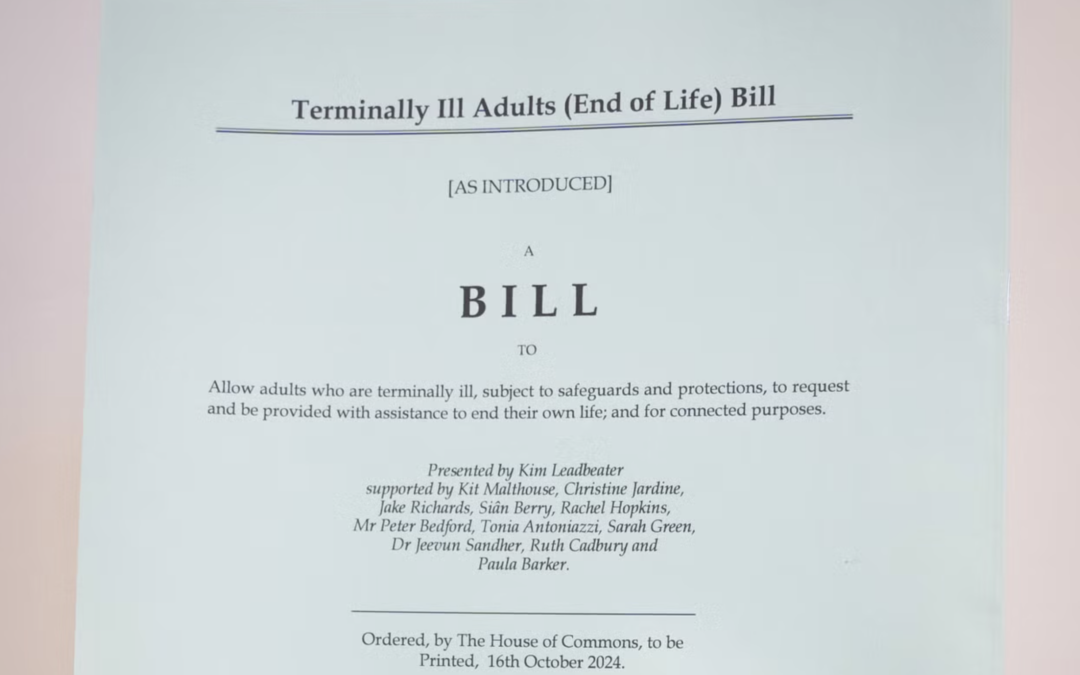

The Assisted Dying for Terminally Ill Adults Bill is due to be debated in the House of Commons on 29th November. The Bill is only for England and Wales but given that Scotland is already considering a Bill and the Republic of Ireland have voted to note a final report by a committee on assisted dying, which calls on the government to legalise assisted dying in certain restricted circumstances, the focus is likely to shift to Northern Ireland should the Bill pass.

Throughout our history the concept of assisting someone to end their life struck at the heart of the values we held as a society. Physicians undertook to care and do no harm and the development of the Hospice movement was a response to the importance of easing the suffering of terminal illness and helping people to die with dignity. Within just a few decades the focus has shifted. In bioethics the principle of respect for personal autonomy has become the defining argument and suddenly even the word dignity has been changed in meaning.

The main means of attacking the current legal framework has been the concentrated emphasis on heart rending instances of an individual’s desperate plight with an incurable illness. This understandably attracts our sympathy and compassion. We can all relate to instances of a loved one’s suffering at the end of life, but for every account of a trip to the Dignatas clinic in Switzerland or there are so many others, where even in the final days and months of life relationships have been healed, important words are spoken and peace is found.

Once Assisted suicide is permitted a whole range of new questions arise which may be an unintended consequence of the initial decision but in essence change the entire health culture, which will affect not only how we as individuals think but also how government makes fiscal decisions. Canada prided itself on the strictness of the criteria it had introduced but when the Quebec Supreme Court decided in 2020 that the exclusion of disability from the legislation was discriminatory, the Canadian government extended the relevant legislation to include mental disorders which did not affect cognitive abilities.

It is difficult to resist the conclusion that stringent safeguards are illusory. This is not surprising. Once the principle is conceded and the Rubicon is crossed, why should the State stop at those with a terminal illness who have less than 6 months to live and wish to end their own lives? The next step to extend the prerogative to those with incurable illnesses who may well have years to live but who feel that life is not worth living. Pressure is already being brough to bear by influential commentators like the retired High Court Judge Sir Nicholas Mostyn who suffers from Parkinson’s and who wish such conditions to be included in the Bill. If the Bill passes how long will it be before the next step is demanded as has almost invariably been the case in other jurisdictions that have changed the law?

It is surely telling that much of the most effective opposition has emerged from those living with disabilities who fear that the change in law means that their lives are less valued. If the Canadian laws are adopted, then any acute suffering per seis potentially a valid ground. Many disabled people identify with the Canadian army veteran, offered medical assisted suicide as a solution to her problem of obtaining a home wheelchair ramp.[1] Are we really saying that it could in any circumstances be legitimate for society to offer assisted suicide to children or euthanasia for the mentally disordered. Yet that is what has happened the Netherlands and Belgium, and it is naive to believe that similar sorts of debate will not happen in the UK in the future should the resent legislation pass.

What we seem to have lost in the clamour for personal autonomy is any idea of the common good or the unintended consequences of legislation aimed at shortening death, but, in reality, opening up a Pandora’s Box where the prevailing culture is changed and it suddenly become acceptable and financially expedient in a healthcare context to discuss euthanasia and assisted suicide as solutions to complex problems.

It is particularly poignant that the greatest opponents of the legislation are those suffering from a lifelong disability who fear that the law on assisted suicide will move quickly to remove the 6-month criterion and include those who suffer from a life long illness[2] . This tells them clearly that their lives are less valued or not worth living.

The current draft Bill permits any medically qualified practitioner of their own volition to discuss with a patient suffering from a terminal illness the possibility of assisting them with their own suicide. Is this not to fundamentally alter the patient doctor relationship? Do we really want our elderly relatives to see themselves as a burden (as 42% of those availing of the procedure in Oregon did in 2022) or think that because of their socio-economic circumstances death would be away out of their misery?

Because I have a moral objection to the legislation in principle it is easy to characterise opposition from a religious perspective as ultra vires and not relevant to the debate. This is wrong because religion is not merely a matter of private opinion but “a vital contributor to the national conversation”. Christianity underpins much of the legal system in the West and in moving decisively in a different direction legislators surely require a better understanding of the alternative world view they are embracing rather than appeals to hard cases and inchoate fervorinos about the absolute sanctity of personal autonomy and choice.

Footnotes:

[1] https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/christine-gauthier-assisted-death-macaulay-1.6671721

[2] Pressure is already being brought to bear by influential commentators like the retired High Court Judge Sir Nicholas Mostyn who suffers from Parkinson’s and who wish such conditions to be included in the Bill.

For more on this topic, click here for the transcript of a recent lecture given by Brett Lockhart KC at QUB, and you can find EA resources on this issue here.

Brett Lockhart KC is a Deacon in St. Bridget’s Church, Belfast.

Please note that the statements and views expressed in this article of those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of Contemporary Christianity.

Brett, thank you for your concise article on the topic. To their credit, I have really appreciated the resources the Presbyterian Church have put together on the topic, available on their website under the heading ‘Living and Dying Well’. The documentary ‘Better Off Dead?’ by the actress Liz Carr, which is available on the BBC iPlayer, also offers a very strong case from a prominent disability activist who is stringently opposed, as you mention above.

Thanks Brett; appreciated

Brett, You give a helpfully concise and coherent rationale to enable a fuller engagement and sharing in open dialogue with family, friends and wider community. THANKS!

My understanding, is that, broadly speaking, there are two main kinds of assisted-dying laws around the world. One type restricts the option to the terminally ill, usually with a maximum life expectancy (e.g. <6 months). The other is broader, usually based on the concept of unbearable suffering.

Canada has a broader law: the result of a Supreme Court ruling. The Government had tried to limit it to those whose deaths were "reasonably foreseeable", but another court ruled that discriminated against those suffering intolerably from a serious incurable illness or disability. I don't think this is the right comparison for what is being proposed in the UK.

Canada's law originated in the courts not the legislature, which could not be the case in UK. Some argue that any law could be expanded by the domestic courts or the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg, but that would be a huge break from precedent. Indeed, in the UK a 2018 Supreme Court ruling against Noel Conway, who had motor neurone disease, made it clear that only parliament could change the law on assisted dying. The case Mortier vs Belgium in Strasbourg made it clear that such issues are a matter for individual states.

My understanding therefore is if parliament were to pass a law on assisted dying, only parliament could change it, by bringing forward new legislation. In 19 jurisdictions in America, Australia and New Zealand etc. with laws restricted to the terminally ill, none have ever broadened?

David

Thank you for taking the time to consider.

I am less sanguine that the initial Bill

if it passes will remain unaltered.

The current proposal is predicated on the premise that the person suffering the terminal illness has the right to request their own suicide and require the state to assist them. The 6 month threshold will be extremely difficult to gauge but in principle when the ‘right’ is conceded it is hard to see why this should be confined to the current time limit There is already pressure from those suffering from acute illnesses such as Parkinson’s to be included in the definition and it is hard to argue against once the Rubicon has been crossed.

Additionally the courts have as you say tended to refer the matter to Parliament but not in every case.

2 of the judges in the Nicklinson case held there was a right to have an assisted death under the framework of the ECHR. Further the Quebec Supreme Court have extended that right to include mental disorder.Canada operates the same common law jurisdiction. I am not at all hopeful that the courts will cede all of the authority to Parliament.

Note also there is nothing in the Bill to include for instance “hopeless and unbearable suffering “‘as in the Netherlands which granted has dystopian laws now including children The UK proposal is only protected by the 6 month limit and the diagnosis albeit to be overseen by 2 doctors and the High Court How on earth the High Court will have the time to adequately and properly oversee is beyond me and why retired judges have spoken out already.

I think we may be about to make an historic error which will further change medical culture and the patient client relationship

Brett, thank you for your reponse. I bow to your legal expertise 🙂

I agree that the 6 month time limit will be difficult to gauge.

However, I still think the Canadian legislature are a poor comparator. I think Mellbourne is better.

I understand the concern over courts ceding all authority to Parliament.

I also agree with the concern over the time available to the High Court.

I flip-flop as it’s a Yes / No vote on imperfect legislation. It’ll always be imperfect 🙁

Internationally, less than 1% of deaths occur through this method.

Interestingly, a large minority who complete the legal process do not go through with the medical process.

The Lords have been debating this every other year since 2014.

Maybe, just maybe, it is time to cross the rubicon.

Thank you for your considered expertise.

David

Thanks again for responding.

My concerns go beyond the fact that the safeguards are in my view illusory. Queensland and Australia generally still in its relative infancy and I wait to see how they will respond when those who advocate personal autonomy as a virtual unqualified right in this sphere get more of the wind in their sails.

What I do know is that Canada is now up to 4.8% of all deaths and Netherlands nearly 6% . These are staggering figures

My main concern is the change in future and what it does to the patient doctor relationship

The current legislation allows a doctor who may not know the patient well to initiate a conversation with someone who may appear to want to take the option Patients repose enormous confidence in the view of a doctor and I struggle to see how one could avoid abuse or coercion. It only takes a few bad actors and we have a problem that can be essentially occluded by the legislation.

I fall back to the old adage that hard cases make bad laws and I cannot help but think that the real pressure for change emanates from a relatively small group of independently minded individuals who subscribe to the view that personal autonomy is sacrosanct. If they could be persuaded that their insistence on their own autonomy was undermining the common good and placing unnecessary pressure on the vulnerable …would they think again.. i fear not and that is a real worry Part of the price of our humanity is that we may need at times have to sacrifice our choices for the sake of the common good and this I think one of those instances Best wishes