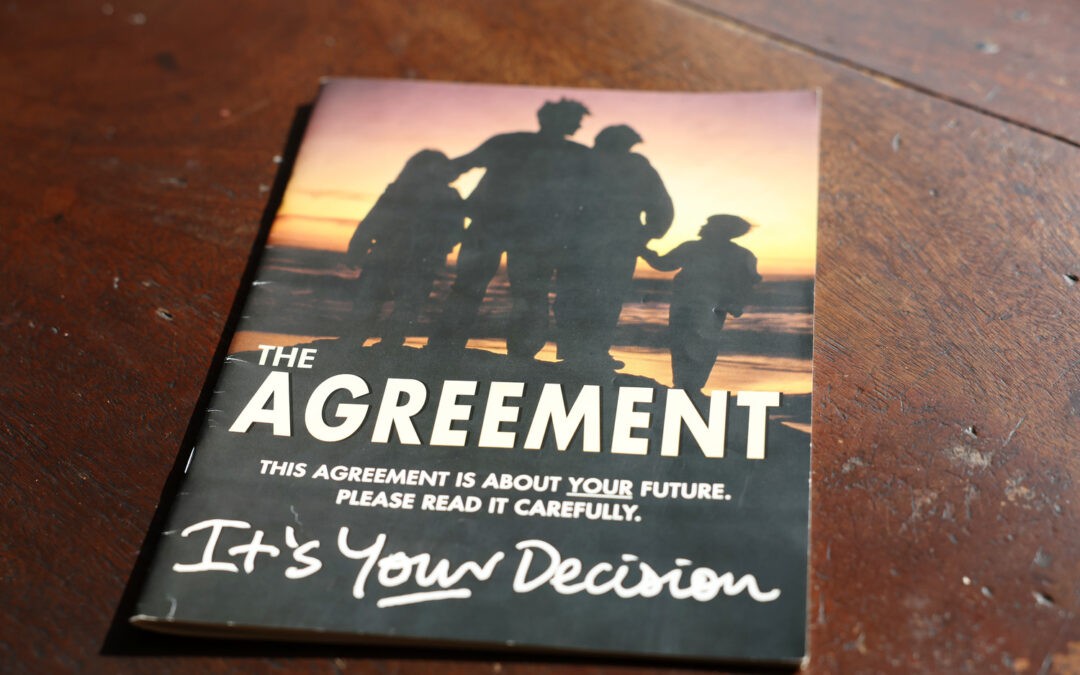

Reflections over the last 25 years since the Good Friday Agreement Referendum Vote (Friday 22nd May, 1998)

The practical problem of Christian politics is not that of drawing up schemes for a Christian society, but that of living as innocently as we can with unbelieving fellow-subjects under unbelieving rulers who will never be perfectly wise and good and who will sometimes be very wicked and very foolish.

– C.S. Lewis

No one expected it would be easy and events on the day itself cast a long shadow over all that was to come. The DUP led protests in the grounds of Stormont and the walkout from inside the talks by members of the UUP team, gave expression to the deep anxiety and fundamental opposition from within the Unionist community.

A combination of political and moral arguments against supporting the agreement began to take hold. Posters appeared from the unionist parties with the clear conviction – it’s right to say no. The declaration and pledge of the united unionists spoke of ‘recoiling with moral contempt.’ An advert in the local press proclaimed with confidence that – it was a sin to vote yes.

Alongside the constitutional and political objections, there was a profound sense that the moral jeopardy involved in making peace not only risked the union, but also would undermine the fabric of society with;

- a place for former terrorists in government without guarantees of decommissioning;

- releasing prisoners, while reforming the police and justice system;

- and legislation to promote a liberal agenda in equality and human rights (not seen to be compatible with traditional Ulster’s values!).

Feminism and gay rights became the new threat to faith, replacing Catholicism as encapsulating all that was to be feared as part of this so-called peaceful future. Of course, for many the issues were strictly political, however this religiously loaded argument played out in churches and homes. For many there was a genuine crisis of conscience – was the price of peace too high?

In 1995, after the publication of the Frameworks Document setting out the scope of a possible agreement, ECONI published “A Future with Hope: Biblical Frameworks for Peace and Reconciliation in Northern Ireland.’ This aimed to provide a Biblical guide to inform a Christian response to any proposals that would emerge from the search for a peaceful settlement. So in April 1998 we issued “A Time to Decide: Responding Biblically to the Agreement” and organised a series of meetings to foster open debate on the referendum ahead.

Then, as now, agreements on paper do not build peaceful communities; it is the people who do this, as Senator George Mitchell has so recently reminded us. At the heart of that task is a commitment to share the future together… living at peace with everyone as far as it depends on us. Our statement invited people on a journey that is still as relevant today.

That journey involves;

- having the courage to escape the burden of guilt and of vengeance and step into the freedom of the forgiveness of God;

- not playing on the tribal fears of our past but putting our hope in God;

- and rejecting the bitterness of division and embracing both neighbour and enemy in the power of the love of God.

All of this pointed to a choice… which still resonates in the rhetoric of our political discourse – do we want to be healed? Amidst all the arguing over legitimate political differences, for 25 years (the Belfast Agreement and much more recently Brexit issues and the Windsor Framework), do we genuinely aspire to a future together in which the deep wounds and trauma of our past can be healed?

The results of the referendum on 22nd May 1998 were hailed as historic, but contained within them an indication of a rocky road ahead. Overall 71% voted yes, but the yes vote within the Protestant /Unionist community was only in the fifties %, and within the Catholic / Nationalist community in the mid-nineties %.

The Brexit sagas over the past 5 years have further eroded Unionism, as evidenced in the two most recent elections.

It is clear that the divisions over land and nationality, with its focus on the border and the legitimacy of the state, continue to create a toxic antagonism that disadvantages us all. The Belfast Agreement was intended to be a ‘fresh start, in which we firmly dedicated ourselves to the achievement of reconciliation, tolerance and mutual trust.’ Acknowledging our differences, ‘we would endeavour to strive, in every practical way, towards reconciliation and rapprochement.’ We voted for peace but we have failed to deliver reconciliation.

The legacy of the violence and suffering of the troubles was a heavy burden to carry. The prolonged dispute over decommissioning, the continued presence of paramilitary groups, the absence of any agreed process of dealing with the past, all contributed to a fragile peace. Set alongside continuing political uncertainty, the weight of the burden seems only to increase. Every violent conflict casts its long shadow over the generations to come. There is an anger that remains in the community.

Reconciliation demands that we deal with that anger, the hate and hostility on which it feeds. Whether in political, religious or cultural terms, sectarianism is the original sin on which we have fuelled our strife.

Reconciliation demands that we address the hurt that exists due to the cycles of violence, not only during the troubles, but also over the centuries. The hurt that we have done to each other is always difficult to talk about never mind find the capacity to heal. We rightly seek truth and justice, but they are harsh masters. They insist that each takes responsibility for their actions and those culpable for choosing to inflict harm are held to account. However, they need to be tempered with mercy if reconciliation is to flourish.

Reconciliation demands that we face the future with hope. There is a desperate need for the church, the people of God, to prophetically speak and act on Jesus’ command to love – love for our neighbour, for the stranger, the alien, and even for our former enemies. If future generations are not to inherit the hostility and pain we need to exorcise the hate, acknowledge the hurt and transform our relationships.

I am convinced that our inability, and perhaps even our unwillingness, to decommission mindsets and to find a way of sensitively opening up the wounds of past and allow deep, inner healing, has prevented us from achieving the kind of conflict transformation envisioned in the Good Friday Agreement and mandated by referenda, north and south, on 22 May that year. Twenty-five years on, we need to keep reminding ourselves that the Agreement was not simply about the cessation of hostilities and the silencing of the bomb and the bullet; it spoke more widely about the building of a peaceful society through a restoration of relationships.– Archbishop Eamon Martin at the Living the Agreement – Legacy Matters Conference

Canon David W Porter was a co-founder and Director of ECONI. He left Belfast in 2008 to lead the international reconciliation ministry at Coventry Cathedral, before being appointed by Archbishop Justin Welby in 2013 as his Director for Reconciliation. He became Chief of Staff at Lambeth Palace in 2016, retiring from that role in November 2022.

Please note that the statements and views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of Contemporary Christianity.

Great article, thanks David. Helpful overview and quote from Archbishop Martin.

Harry are you the Harr I knew when I was a minister in Taughmonagh church many years ago? If so, I would love to meet up with you somehow. I am now living in Carricffergus and on Facebook, messenger. If you contact me, I have no problem giving you my phone number et cetera.privately

I agree with your comment on the article also. And would love to have a coffee with you. Oul mait

Blessings. Bill, Moore.

I am frustrated at the lack of progress for integrated education. The grammar school system fosters an unhealthy attitude of superiority and an alarming lack of knowledge of how the majority of of the population live.The rich are becoming richer and the poor are becoming poorer.