As a ‘ceasefire baby’ I have no specific memory of that Good Friday! What I remember instead is referendum day. On 22 May 1998 concurrent referenda were held in Ireland and Northern Ireland to, in essence, approve the terms of what is now called the Belfast ‘Good Friday’ Agreement. At the time, my maternal grandmother was in hospital awaiting major surgery and was under a strict bed rest policy. Being a feisty woman, and aided by the diplomatic skills of my mum, my gran defied the ‘bed rest’ writ. She temporarily broke free from the confines of the Ulster Hospital, so as to be able to vote a resounding ‘YES’ in response to the question asked of the Northern Ireland electorate on that day: “Do you support the agreement reached at the multi-party talks on Northern Ireland?” A child at the time, I have a vague memory, one inevitability informed by retrospective adult thought, of accompanying my mum on a transport mission that felt both important and illicit in equal measure.

By voting ‘YES’ on that 1998-day, my gran joined with the respective 71% and 94% majorities North and South of the land border that, in effect, approved the terms of the 1998 Agreement. A new era of fragile peace in Northern Ireland was, thereby ushered in.

As the eyes of the world have turned to Northern Ireland over the last few weeks, I have thought much of my gran’s determination to exercise her democratic right those 25 years ago. Although I could not appreciate it at the time, from what I now know, her defiance of ill health and in support of an imperfect compromise, was a vote for the hope of a better future and a better Northern Ireland for others and me like me.

In the words of the Agreement that collective constitutional moment in 1998 was one that, offered “a truly historic opportunity for a new beginning” (Declaration of Support Item 1) through which the people of “these islands” dedicated themselves to the achievement of reconciliation, tolerance, and mutual trust for the cause of us all.

In my understanding, the 1998 Agreement and the confirmatory events that surrounded it at the time, constituted a promise to and commission for the generations that would grow up in the long-awaited light of the peace that was to follow. Unfortunately, 25 years on, the promise and commission has arguably been neither fully realised nor well stewarded, although determining this depends somewhat on how we conceptualise peace.

If ‘peace’ is absence of violence the 1998 Agreement has largely achieved its goal. If ‘peace’ is reconciliation, restoration and redemption of broken relationships, the 1998 Agreement has fallen far short.

Traditional ‘green-orange’ divisions are still all too visible in Northern Ireland society. A binary split remains embedded in our political institutions, reflected in our education systems, inscribed on our gable walls, and infused in our ecclesiastical structures. Making Northern Ireland today a place that is comfortable with and defined by disunity. As followers of Jesus, this should disturb us.

A scripturally informed definition of peace is comprehensive. The Hebrew word shalom translated as peace in the bible connotes a beautiful, holistic vision for restoration. Beyond a mere end of hostilities, shalom, biblical peace, is multidimensional wholeness. It is used to describe reconciliation with God (Numbers 25v12), reconciliation with others (1 Kings 5v12), an absence of injustice and oppression (Jeremiah 8v11) as well as an individual psychological peace of mind and spirit (Isaiah 32v17).

Looking at contemporary Northern Ireland, it is hard to make the case that shalom peace between the previously warring ‘two communities’ of Catholic/Nationalist/Republican and Protestant/Unionist/Loyalist has been achieved. True peace takes time, dedication, and graft – there is still much work to be done.

Scripture commissions Christians to join with the Lord in the work of reconciliation of all things (2 Cor 5v11-21). For the church in Northern Ireland this holy mandate ought to weigh on us, maybe more than it currently does, or has done these last 25 years.

More than anywhere else in the UK or Ireland, the pain wrought by the absence of peace in its narrowest sense is known in Northern Ireland. The desire to end that pain, I believe, motivated my grandmother’s minor rebellion in May 1998 to vote ‘YES’ along with the overwhelming majority of the electorates across this land. In the years since, we – the Northern Ireland church and Northern Ireland society more generally – have perhaps become weary or worse apathetic in the pursuit of peace in its broadest sense.

As the dust settles, in the wake of commemorative events… Presidential motorcades, and dignitaries’ photo-ops, there is a need for us all, but particularly those who proclaim the name of a God – who calls us into the work of peace-making, to reconsider the part we must play in bolstering the “still-in-process” fragile peace which we have all been living in for the last quarter century.

Lisa Whitten is a Research Fellow at The Queen’s University of Belfast. She completed her Doctoral dissertation last year on the constitutional implications of Brexit for Northern Ireland. Prior to that Lisa held a variety of posts in the political and public sector including working for the Office of the Northern Ireland Executive in Brussels and for a Member of the UK Parliament in Westminster. Lisa is a Contemporary Christianity Board member.

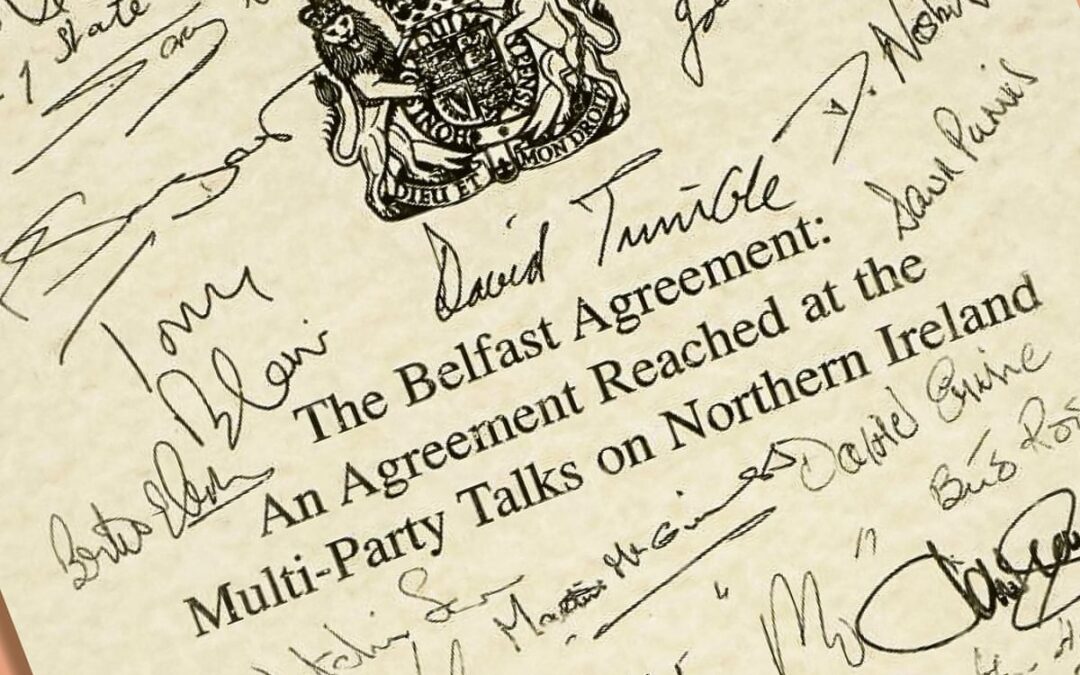

This article is part of a series marking 25 years since the Belfast Agreement/Good Friday Agreement that was signed on 10th April 1998. To view other articles that relate to the Agreement, please click here.

Please note that the statements and views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of Contemporary Christianity.

What about NT reconciliation – Romans 5:11 and 11:15 and also 2 Cor 5:18,19. Do they not figure somewhere!

I can all look back at how in business I might have made better agreements but I will always seek to stand by whatever I agreed to

With elections coming we need to hold politicians to account and NOT elect any who will not stand by what the people have agreed in the Good Friday agreement