The person who had no such qualms on speaking out was Ian Paisley, yet his interpretation of the Bible seemed to twist Scripture to suit his political agenda and it was hard to see much of Jesus in his bitter rhetoric of conspiracy and betrayal. This was why the emergence of ECONI in the mid-1980s was such a breath of fresh air.

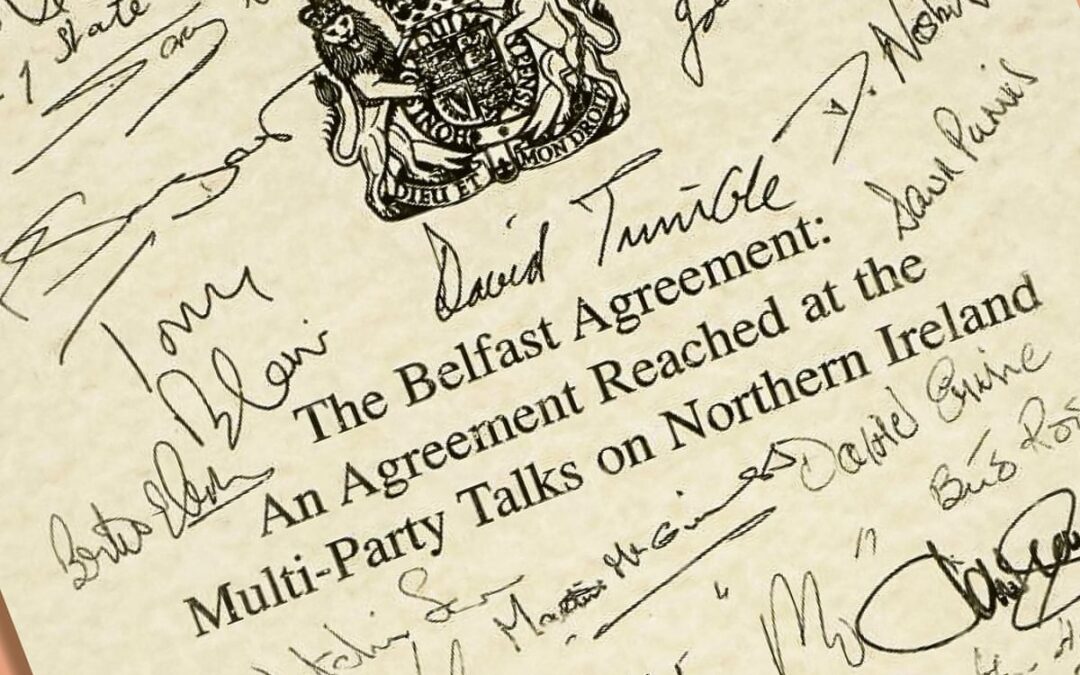

That puzzlement turned into an undergrad dissertation and, later, into a PhD and eventually a book, Evangelicalism and National Identity in Ulster 1921-1998 (Oxford University Press, 2003). I chose 1998 as the end point of the study in that the Good Friday Agreement (GFA) was clearly a significant moment in Irish history. Being asked to write this PS prompted me to go back and read the book’s conclusions. I asked then,

How successful the Agreement will be in achieving its aims raises a number of open questions likely to remain valid for years to come. Can two opposing forms of national identity co-exist in prolonged co-operation within one devolved government? Can unionists find security despite an unsecured Union? Can nationalists achieve, and even be content with, political, cultural and economic equality within a transformed Northern Irish society?

It seems to me that today those questions remain as open as ever. A pessimist might answer ‘No’ to each one. ‘The last 25 years have revealed the inherent contradictions and fudges within the GFA. The institutions are paralysed and Northern politics are not working. The struggle between nationalists and unionists is as intractable as ever.’ An optimist might say ‘Hopefully, yes, we are getting there. The last 25 years have been far from perfect, but peace and trust take time. There is hope we can get beyond the zero-sum competition between unionism and nationalism. There is no way we are going back to the past.’

I also argued that the GFA, despite its intended impartiality, raised much more uncomfortable questions for unionists than it did for nationalists. Full equality for nationalists would inevitably weaken unionist identity and the British ethos of the state. While the GFA formally recognised the principle of consent, it made the Union more vulnerable than before. Instead of being guaranteed by the British government, it now rests solely on the will of a majority. While a future nationalist majority does not equate to a vote in favour of a United Ireland, long-term demographic trends for unionism remain ominous. As someone has said, the scariest thing for unionists about the GFA is that there is no full stop. Unionists also face the dilemma that even wholehearted participation in the structures of the GFA carries no guarantee of securing the Union and may even undermine it. This is what ended the career of David Trimble and put Ian Paisley in power. Ironically, the DUP now face the same conundrum, only made worse by the self-inflicted damage to the Union wrought by a DUP-backed Brexit. Their current strategy of withdrawal from the assembly is not a viable alternative and only further alienates unionist support – let alone failing to govern for the good of the electorate.

So unionism faces a deeply uncertain future and I think most unionists know this, whether they say it aloud or not. In saying this, I’m not making value judgments, just describing things as I see them. If accurate, it seems to me that if the defining challenge twenty-five years ago for unionism was entering power-sharing with Sinn Féin, the coming challenge will be to face up to the likelihood of further constitutional change – whatever that might look like. That will be a task not only for unionist leaders but for denominational and church leaders as well. A Christian’s identity rests in Christ, not in the fortunes of any political identity. Unionism has been defined by a pessimistic siege mentality, but fear and defensiveness are not Christian virtues – faith, hope and love are.

Recent Comments